New Public Art Project for the San Diego International Airport

Read MoreColumn design concept

Column design concept

New Public Art Project for the San Diego International Airport

Read More

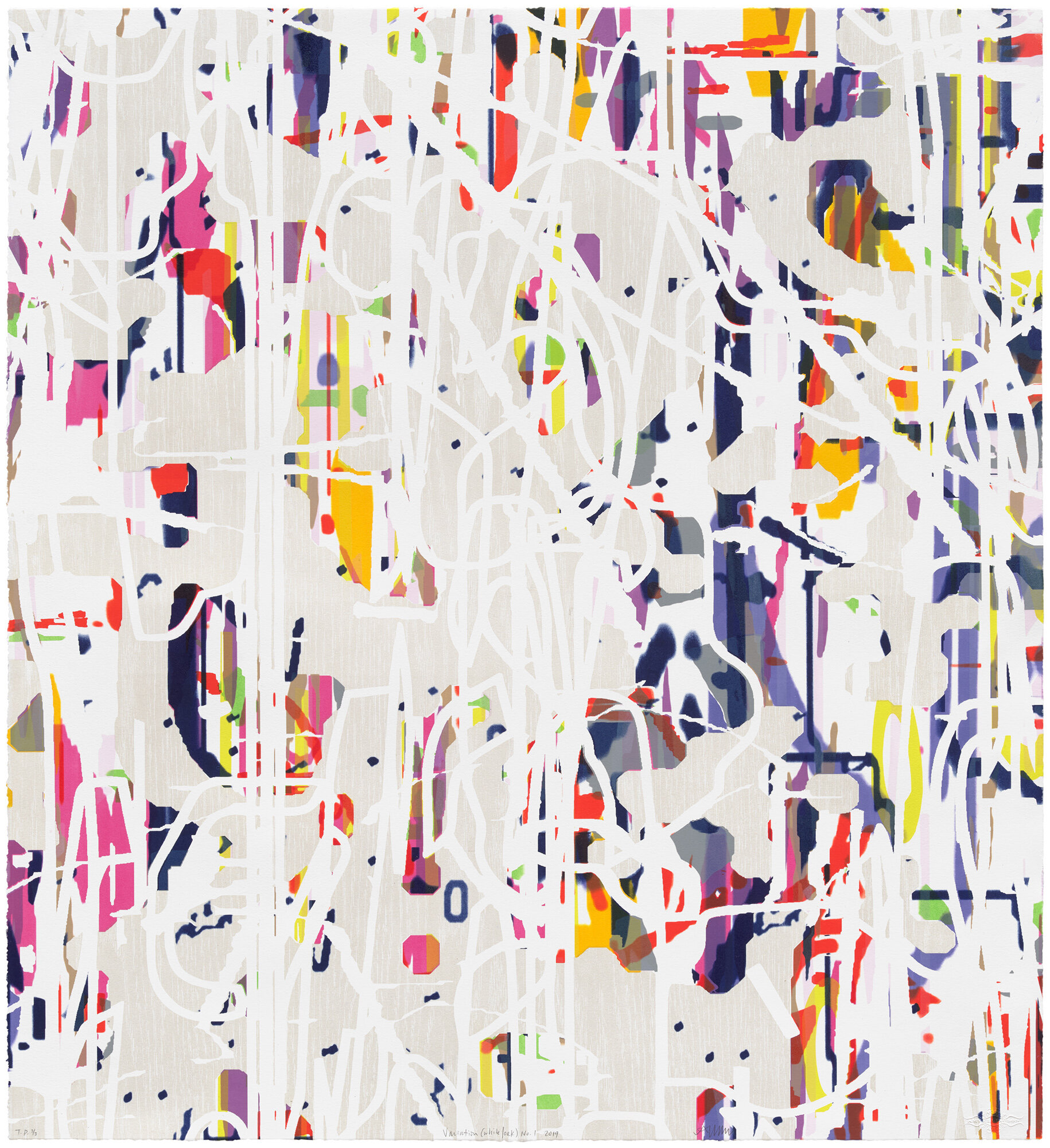

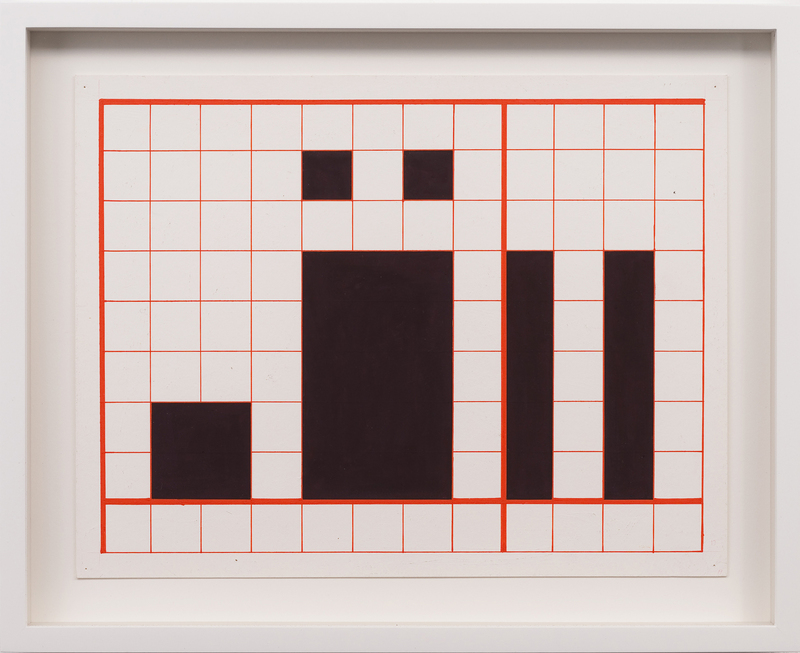

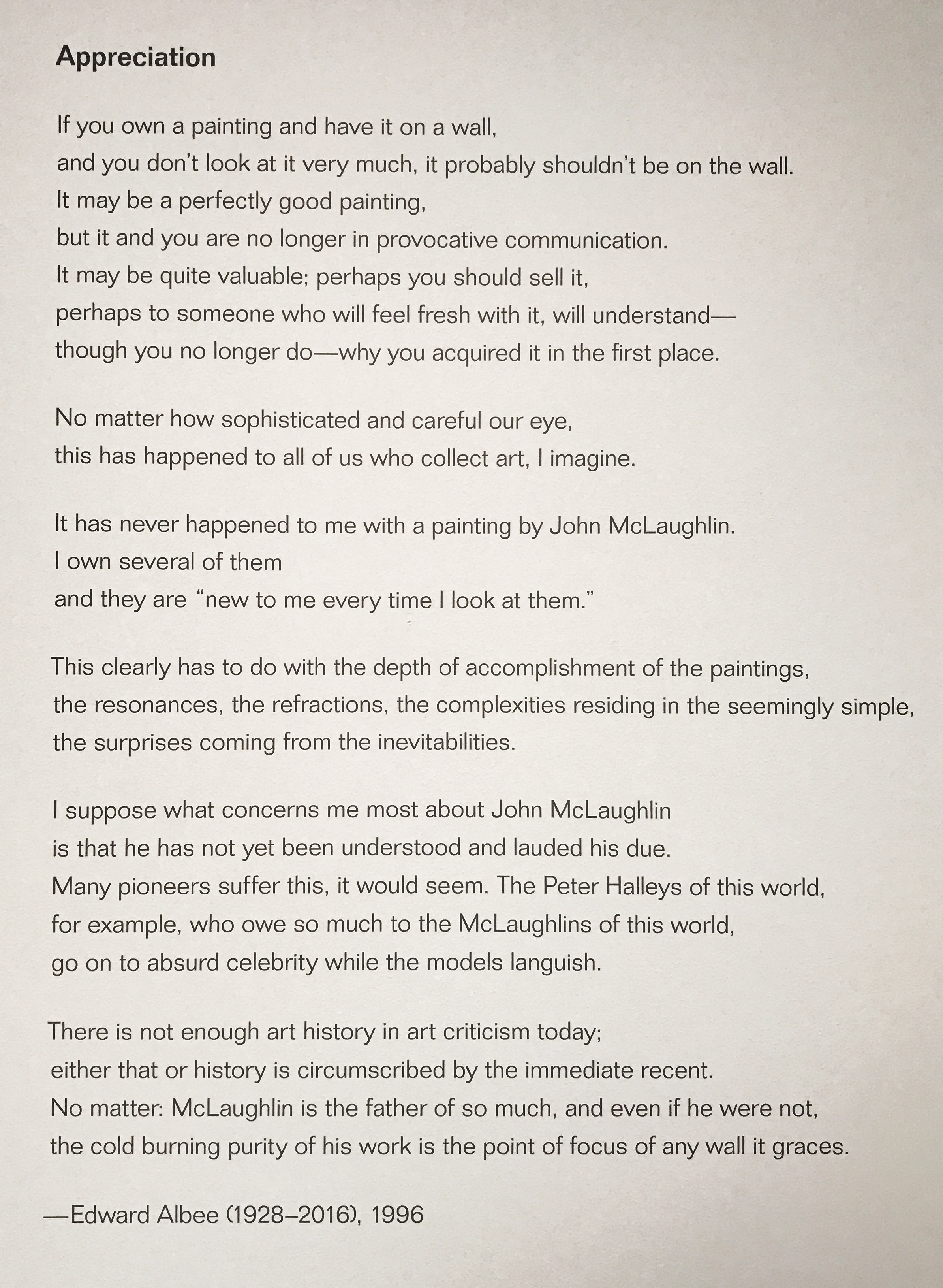

Variation (white/oak) Nos. 1 & 2, 2019

Twelve color lithographs on Rives BFK, each 32 ¾ x 30 inches

Early in March 2019, I received an email from Bud Shark at Shark’s Ink. in Lyons, Colorado, asking if I might be interested in doing a print project with him. Bud and his wife Barbara have been running Shark’s Ink. since 1976, and have collaborated with a stellar group of more than 160 artists from the United States and Europe over the years. Bud’s email arrived during the short, dark days of my first winter in Santa Fe. I was awaiting the completion of my new studio and was beginning to feel a bit of frustration along with the excitement and anticipation of having a new workspace, so it was the perfect moment to begin to wrap my mind around a collaborative print project.

Bud and I began an easy correspondence, sharing ideas and figuring out an ideal time for me to visit the studio. We settled on the last two weeks of August 2019, and I began to work on ideas for the prints. At the beginning of May, my studio was finished, and I began the task of moving, unpacking and settling in. All the while, ideas percolated in the back of my mind for new prints. By July, Bud and I were in constant contact, with a flurry of emails back and forth. Since printmaking is still fairly new to me, I relied on Bud’s expertise to assess how my images might live as prints. For me, the most exciting part of working in another medium is learning the nature of that medium, and figuring out how to take advantage of its unique qualities, characteristics and processes.

I left Santa Fe and spent a couple of nights in Denver before heading up to Lyons. Since I’d spent many months at home, overseeing the studio project, it felt wonderful to be on the open road. The drive to Colorado is gorgeous, and I couldn’t help but prop my phone on the steering wheel to take a few shots of the single-point perspective landscape. It is one of my favorite things about living in this part of the country.

In Denver, I had a long meeting at Robischon Gallery that ended late in the afternoon. I had just enough time to dash over to the Denver Museum of Art to see the exhibition Jordan Casteel: Returning the Gaze, and also The Light Show, before racing over to the Clyfford Still Museum to make my regular pilgrimage to see the 1953 letter that Still wrote to Jackson Pollock.

Dear Jack,

Went up to Janis’ gallery with Barney the other day & took the liberty of pushing into the office to see some of the paintings you did this summer.

What each work said, what its position, what each achieved you must know. But above all these details and intentions the great thing, to me, came through. It was that a MAN had been at work; at the profoundest work a man can do, facing up to what he is and aspires to. I left the room with the gratitude & renewal of courage that always comes at such moments. This is just my way of saying thanks, & with the hope some of my work has brought some of the same to you.

Clyff Still

Sure, the emphasis on the word man gives me pause. But I think Still meant it in the spirit of individuality. As an artist, the thing that gives me courage, and the thing that makes life worth living are the interactions between artists, both in real-time and through time. So, Pollock’s works spoke to Still, Still responded in writing to Pollock and, through this letter (and the sum of their paintings and their lives) they both speak to me and to anyone else who might be listening.

I arrived at Bud and Barbara’s at lunchtime on August 18. Barbara’s skills as a great cook are well known and, after quick introductions, we sat down to a delicious lunch on the patio at the front of their home, overlooking a little valley, with a big mountain range in the distance. Bud and I got to work that afternoon. What follows is a diary of the project, based on my studio notes and photos, accompanied by notes on Barbara’s exceptional meals.

The view from the top of the driveway. After long days of close work at the computer and the work tables, I loved being able to focus my eyes on the mountains in the distance.

Day 1, August 18

After lunch (zucchini soup, served with fresh bread with ricotta, cucumber and fresh peach) Bud and I walked over to the studio and began to plan our strategy for making the prints. We printed the image for the first print on the laser printer. Because the printer has a maximum printing size of 11x17 inches, while my print would be 33x30 inches, we tiled the image and taped it together. After deciding that the woodgrain “background” would be the first plate, we tested woodgrain patterns and colors. Luckily, Bud had some nice sheets of oak plywood with a beautiful grain on hand. He mixed up some ink and we tested the color and texture, finally arriving at a combination that had just the right amount of texture, color and value to work with the white of the paper and the super-saturated, bright colors that would follow.

Test print, showing the woodgrain plate in contrast with the white paper. We worked to get the color and value just right.

We then printed out the full image again, replacing my temporary faux woodgrain (that I had created in Photoshop) with a bright cyan blue. Satisfied that we had a plan of action for Monday, we had dinner, chatted and read before bed.

Day 2, August 19

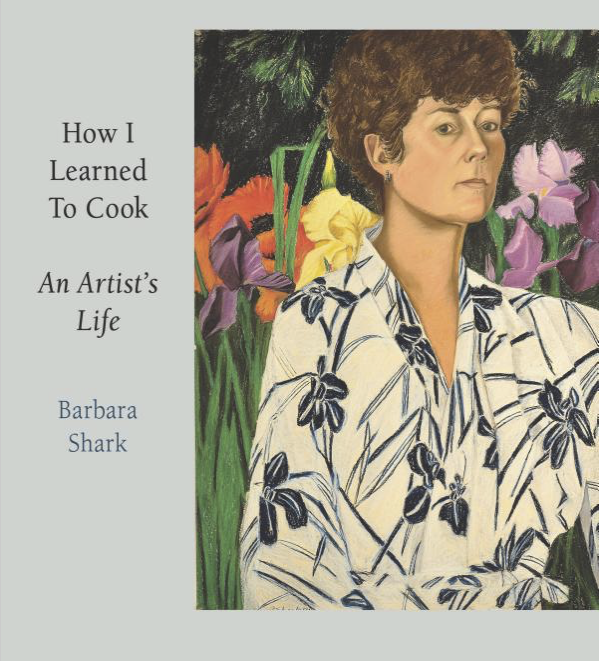

Barbara is an artist, writer and, as mentioned, a fabulous cook. Breakfast was the same every day—exquisitely the same! Barbara's breakfast is my preferred breakfast, so I was thrilled by the daily offering of homemade granola, homemade yogurt, Colorado peaches and blueberries, along with a tall French press coffee. I soon learned that Barbara spent a couple of years writing her book, How I Learned to Cook: An Artist’s Life, a combination memoir, art book and cookbook, with reproductions of 85 of Barbara's paintings and drawings, along with 105 of her recipes accompanying a narrative of her journey with Bud and the artists they’ve worked with over the years.

After breakfast, Bud and I picked up where we left off, laying a sheet of mylar over the printout with the cyan in place of the woodgrain. We’d need to black out all of the woodgrain areas so that we could make the plate. First, we carefully traced around the woodgrain areas with mechanical pencils. Then, we painted all of these areas out with black acrylic paint. Bud and I spent about 10 hours working on this. It rather reminded me of being a kid and working on a school project with a friend. There’s a lot of intimacy and time to talk about anything and everything when working on a task like this, with heads bent, eyes focused and hands busy.

After a long day, we sat down to a delicious summer meal of grilled salmon, corn, potato salad, homemade pickles, tomatoes and a lovely dish of golden beets served with their greens and a dollop of homemade yogurt.

Day 3, August 20

When I built the files for the prints, I composed them in my usual way, as if they would be paintings. Once Bud and I began looking at them more closely, I realized that I would have to reorder the colors. Typically, the lighter colors are printed first, so there was a lot of reshuffling and editing to be done to make them more suitable to the process, without changing the overall feel of them too much. While I busied myself with the files and prepping the second set of mylar, Bud and his longtime printing assistant, Evan Colbert, began working on the first plate. Evan measured and tore down ten sheets of paper, slightly larger than the finished size of the prints. Of these ten sheets, we knew we would lose a few to mistakes along the way, such as misaligned registration, colors that might have to be adjusted, etc.

Bud inking the first plate. He applied several very thin layers of ink, while Evan stood on the opposite side of the press and wiped the plate with a wet sponge.

By late afternoon, the first plate printed was printed.

The remainder of the day was spent preparing the mylar for yellow, the second color. It took us a while to get a good system down, but by the end of the day, we were feeling more comfortable with our process of printing, assembling and correcting the mylars.

Day 4, August 21

Bud and Evan printed the yellow, but we had some registration issues and lost a number of the prints, so we had to replace them. Evan tore down five more sheets of paper, and we printed the woodgrain layer again. Now, with ten prints to work on again, we were up and running. I printed out the mylars for the next color, green, while Bud and Evan printed layers one and two. I am always amazed at how different ink is from other mediums I am familiar with. It’s so saturated and intense, but also tends to be more transparent due to the thinness of the application. The white of the paper sets the colors alight. Evan is a masterful color mixer, and he pretty much nailed each color on the first try, without fail.

A pure citron yellow.

Two colors down!

Soon a nice rhythm developed amongst the three of us. I tweaked my files and printed and laid out the mylars, while Bud burned plates and Evan mixed ink. Bud and Evan work together like the perfect machine. Evan seemingly reads Bud’s mind and is there, in the right spot, doing the right thing, at the perfect moment, with very little discussion along the way, except for the exchange of “yeah” and “yeah” when the paper is perfectly placed on the plate and the press is about to engage. At one point, Bud tossed a sponge in the air, which Evan caught without looking. It was like watching the perfect stealth football play.

The day ended with Barbara’s delicious summer pasta, served with chunks of brie, fresh tomatoes and herbs, and a big salad.

Day 5, August 22

Now that we had established a good system and rhythm of working, I had a bit of time to watch Bud and Evan printing. As mentioned, the two of them work as one. When they are printing, the studio suddenly goes quiet, and one can feel the increased level of concentration in the air. Bud’s body language changes; his confidence, expertise and precision are evident in every move he makes. Suddenly, there is an economy of movement that feels athletic; it’s like watching two teammates who’ve played a sport together for a long time. It goes something like this: Bud: ink, ink, ink. Evan: dip righthand sponge, squeeze righthand sponge, wipe righthand sponge back and forth 12 times, covering the plate. Bud: roll. roll, roll. Evan: wipe lefthand sponge back and forth 16 times. Place paper over the plate on the press. Check the marks at top and bottom. Evan: “Yeah.” Bud: “Yeah.” And… print! In between all of these steps, Evan might have 30-second increments of downtime. He uses these spare moments to peruse a big stack of cookbooks that he borrows from the library. He keeps this stack on one of the workbenches. Nearby, he has a scrap of paper on which he notes his menu ideas and grocery list for dinner that night. We had a lot of fun discussing gardening (Evan is a pepper fanatic, growing dozens and dozens of hot pepper plants every year), cookbooks and recipes.

By the end of the day, we had printed three more colors. We enjoyed Barbara’s shrimp and peach tacos for dinner, accompanied by poblano peppers stuffed with corn, breadcrumbs, cheese and piñons.

Day 6, August 23

At the beginning of the first week, we were doubtful that we’d be able to complete two prints in our two weeks together but, by Friday, things were humming along well enough that Bud felt confident that we’d be able to finish a second print, so I jumped into working on the file, while Bud and Evan printed three more colors on print #1, which was beginning to shape up nicely.

Dinner: Nicoise salad.

Day 7, August 24

While I continued to work on the file and the separations for print #2, Bud and Evan printed two more colors (orange-red and midnight blue) which completely transformed the print. Although we’d been printing up to three colors each day, we decided to let the prints thoroughly dry before printing the very last color (very pale lilac) on Monday.

We had a very special dinner that night, with several Colorado artists (Kate Petley, Kim Dickey and Ana Maria Hernando) art historian Kirk Ambrose, and Bud and Barbara’s daughter, Zöe Shark, who’d just returned from a long trek in Peru. It was a wonderful evening, and so lovely to be introduced to such talented and interesting people. Barbara’s dinner: smoked coho salmon, quinoa with cherry tomatoes and corn, grilled zucchini and squash with parmesan and nuts, Zuni Cafe’s recipe for olive relish, walnut focaccia and peach tart for dessert.

One more color to go!

Day 8, August 25

We’d been going full speed all week, and had decided to work through the weekend, but since it was Sunday, we started a bit later in the morning and stopped a bit earlier in the afternoon. Bud and I completed painting out the knock-out layer mylar for the woodgrain plate, which was our big task of the day.

Sunday evening, we went to a dinner party hosted by Kate Petley. Kate and her husband Mark graciously hosted a terrific group of people for a big sit-down dinner at their lovely home. We were able to sneak down to Kate’s studio to see works in progress, too! I so enjoyed meeting this fine group and felt so welcomed by everyone. It really was a night to remember.

Day 9, August 26

Today we completed the first print! We printed the final color, a very delicate transparent lilac. After a brief pause to evaluate the finished print, we jumped right into the second one, printing both the woodgrain and the yellow after lunch. Dinner: pork tenderloin, olive relish, tomato and cucumber salad, sweet potato with lime, corn on the cob.

Day 10, August 27

Bud and Evan printed two colors (green and yellow-orange) before lunch, while I continued working on the separations. After lunch, they printed one more color (pink). Now that we were well on our way with the second print, we could breathe a little. Bud suggested that we go on a hike in the late afternoon. It was so nice to be outdoors, moving our legs! We walked along the trail to Button Rock Dam. It was a gorgeous afternoon and it was wonderful to see a bit of the area.

Day 11, August 28

I continued to work on the mylar separations, while Bud and Evan printed three more colors (purple-pink, grey and brown). My work on the mylar layers was beginning to wind down. Roseanne, Bud’s longtime assistant who handles all the sales, correspondence and promotion, as well as all of the packing and shipping of prints, took the time to show me some of the many editions in the flat files. The files had been recently reorganized, after the major undertaking of transferring the Shark’s Ink. archive—known as the Sharkive— to the University of Colorado Art Museum in Boulder. The collection covers the printmaking process from beginning to end, including over 700 signed limited-edition prints and more than 2,000 related materials including artist studies, trial proofs, unique proofs with paper alternatives and artist and printer’s notes and correspondence. After inventorying, documenting and packing up prints and related materials for the University, Bud and his team completely reorganized the editions that remained in the studio. Roseanne knows the location of each and every print, and she expertly and carefully opened drawers and pulled out various prints for me. The breadth of Shark’s Ink.’s collaborations is astonishing. Over the years, Bud has worked with many notable artists, including John Buck, Enrique Chagoya, Red Grooms, Jane Hammond, Robert Kushner, Hung Liu and Betty Woodman, among others.

Dinner: spatchcocked chicken, tomato salad with peaches and herbs, zucchini-onion gratin.

Day 12, August 29

Bud and Evan printed the violet and the orange-red before lunch. After lunch, they printed the midnight blue. One color to go! Dinner: tomato and cheese tart, lentil salad.

One color to go, but we’re nearly there. Of course, the prints need to be torn down, which will make a big difference.

The deck off of the studio.

Barbara’s garden.

Barbara making a cheese and tomato tart.

Day 13, August 30

Bud burned the final plate this morning. We printed the last color (pale lilac) before lunch. After lunch (black bean and cheese tacos, divine cookies, melon slices) we tore down and curated the prints. Meanwhile, Evan began preparations for the next artist, Enrique Chagoya, who was scheduled to arrive on Monday. Finally, Bud and I signed and chopped the trial proofs. Of course, all the hard work of printing the editions is still to come; Bud and Evan will complete the prints this November. Bud packed up two prints for me. Evan and Roseanne left a bit early, and I realized that I had not even had a moment to explore the charming town of Lyons during my stay, so I dashed downtown for a couple of hours. Of course, I needed a souvenir, so I bought a beautiful coyote skull in an antique shop. Our final dinner was bittersweet. I’d had such a wonderful time with Bud and Barbara and the team. Barbara made bucatini with sautéed vegetables, goat cheese and candied walnuts, along with a salad of tomatoes, green beans and golden beets. We said our farewells and I packed up so that I could leave for the long drive home at six the next morning.

I am so grateful to everyone at Shark’s Ink. for this wonderful and memorable experience.

Selfie with Evan!

Variation (white/oak) No. 1 , 2019, twelve color lithograph, 32 ¾ x 30 inches

Variation (white/oak) No. 2 , 2019, twelve color lithograph, 32 ¾ x 30 inches

Late last month, after a short trip to Montreal to work with Mosaika Art & Design on my commission for a new public art project, I took the train to NYC for a couple of meetings and a little bit of gallery hopping. My time in New York was very compressed, and I only had 5 hours available on Saturday, September 28.

When I have an abundance of time, I tend to immerse myself and see as much as possible—the good, the bad and the ugly. My Beloved refers to it as the “Art Death March.” However, with time so short, I prepared a very concise, detailed list that took me to the Upper East Side, the Lower East Side and Chelsea. Of course, I planned my subway trips and my Uber ride in advance, as well as the order of my stops and even my strategy for walking and crossing streets, as I didn’t want to waste a moment. Also, I set a very particular agenda for myself; I wanted to leave New York feeling inspired.

Here’s a summary of what I saw. Many of these shows are still open as of the date of this post. See them if you can!

Alma Thomas: Resurrection, Mnuchin Gallery, through October 19

What a place to start! If this had been the only show I’d seen, I would’ve left New York feeling happy and fulfilled. This beautiful exhibition was curated by Sukanya Rajaratnam. It is comprehensive, with major works as well as a good selection of works on paper. Thomas’ energy and pure spirit shines through every piece. Of course, her story is astonishing. She did not paint full time until she was in her 60s, after teaching in Washington DC public schools for thirty-five years, but she more than made up for lost time. Her work is personal and historically resonant, connecting to Abstract Expressionism, Pointillism, Color Field and Minimalism.

Thomas was the first African-American woman to have a solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and she enjoyed success late in life. Since her death in 1978 and, especially, in recent years, her contributions have been reassessed, and she’s finally getting her due.

I love this direct reference to Matisse’s work, The Snail. I wish I knew how and why Thomas took on

this challenge, but I imagine that it is the peculiar puzzle of the sheer stability of the framework with the rotational, destabilizing movement of the multicolored forms.

Matisse, The Snail, 1953.

Thomas’ version, from 1965.

This piece is pure eye-sizzle. many of Thomas’ works take advantage of optical tricks that fry one’s eyeballs as much as any good Op Art masterwork.

The exhibition includes a few wall-sized photos of Thomas, along with quotes by the artist.

Gorgeous, full-wall installation of paintings and framed works on paper.

Another photo of the artist on one of the gallery’s curved walls. Thomas died in 1978.

Richard Serra: Triptychs and Diptychs, Gagosian (980 Madison Ave.), though November 2

Serra’s triptychs (47.5 x 93 inches) and the diptychs 47.5 x 62 inches) are nothing more, nothing less than groups of pitch-black squares or rectangles, abutting each other and/or adjacent to each other, with the white space of the paper somehow holding equal importance with the black, scumbly forms. The shapes are thick and tar-like, made with paint stick, etching ink and silica on handmade paper, with a few spatters and speckles of black adorning the otherwise pristine, heavy white paper. Throughout, there is a sense of exquisite balance and materiality. In Serra’s own words:

Weight is a value for me—not that it is any more compelling than lightness, but I simply know more about weight than about lightness and therefore I have more to say about it, more to say about the balancing of weight, the diminishing of weight, the addition and subtraction of weight, the concentration of weight, the rigging of weight, the propping of weight, the placement of weight, the locking of weight, the psychological effects of weight, the disorientation of weight, the disequilibrium of weight, the rotation of weight, the movement of weight, the directionality of weight, the shape of weight.

Zao Wou-Ki, Gagosian (976 Madison Ave.), through October 26

I received a press release email for this exhibition a few weeks ago, and thought it sounded intriguing, My gallery jaunt mostly included artists who were already familiar to me, but I don’t believe I’ve ever seen works by the Chinese-born, French painter Zao Wou-Ki till now. The works, produced from 1979-2006, serve as a missing link between traditional Chinese painting and Abstract Expressionism. Like Pollock, Zao Wou-Ki worked on the floor, painting with ink on paper (later mounted to canvas). The marks are soft and subtle. Even the darkest, blackest marks are somehow elusive and fleeting. I kept thinking of spurts of squid ink in the deep ocean, flowing, billowing and dissipating. The largest works are about nine feet tall. The soft, matte surface of the paper, with the ink held in rather than on the fibers of the substrate, is so absorbent that your gaze, too, falls into it, rather than skipping over the surface.

John Chamberlain: Baby Tycoons, Hauser & Wirth (69th St.), through October 19

Chamberlain is rather hit or miss for me. He lost me after his early, iconic works. At a certain point, his forms became less dynamic (more vertical, static and monolithic) and his color application seemed more arbitrary (more decorative). At the same time, the sculptures felt overly complicated, with narrower strips of metal that felt superfluous or overly fussed over. However, after seeing a few images of the Baby Tycoons, I thought the exhibition would be worth a visit. First, the title: it all but screams, “Baby Tycoons, here’s something you can afford! Cute little tabletop versions of my big sculptures!” Ah, but I sound cynical (which I am not). Anyway, these little guys pack a real punch. They morph from every angle, they hum with every aspect and shift of color, edge, angle, interior and exterior. They sit like little creatures on their pedestals, full of vim and vigor. As Chamberlain said,

If the scale is dealt with then the size has nothing to do with it.

Forms Larger and Bolder: Eva Hesse Drawings from the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College, Hauser & Wirth (69th St.), through October 19

This comprehensive exhibition of approximately 70 works on paper from the 1960s includes Hesse’s very early student work (figure studies, still life drawings) as well as more experimental abstract works from 1964, which she described as “wild space” in a letter to Sol LeWitt, and a good number of working sketches and studies for sculptural works. This show is geared toward Hesse wonks, providing a terrific sense of Hesse’s early trajectory, working methods and thought processes. Individual works are not necessarily mind-blowing but, as a whole, the exhibition lays foundation for Hesse’s more widely known and appreciated sculptures.

One of Hesse’s “wild space” works from 1964.

Ron Gorchov: at the cusp of the 80s, paintings 1979-1983, Cheim & Read, through November 15

This was my first visit to Cheim & Read’s new Uptown digs. It’s a lovely space, though so much smaller and more intimate than the old space in Chelsea. It feels a bit too small for Gorchov’s powerful, aggressive paintings. Much has been written about the structure of his shaped canvases. Yes, they resemble shields and masks. However, on this visit, another analogy struck me: the reference to saddles, thus making the primal associations more even complete, more fulfilled. These works are meant to do battle, to seize, to conquer! They will not lay down arms before any friend or foe! In the confines of Cheim & Read’s new space, they were a band of warriors, poised for attack.

Friedel Dzubas: Affective Color, Yares Art, through November 2

I’m a big fan of Yares Art’s Santa Fe outpost. In New York, the gallery occupies McKee Gallery’s as well as Mary Boone Gallery’s old spaces on Fifth Avenue. The gallery specializes in Color Field painting, so of course it was a necessary stop, even though I was unfamiliar with the artist featured in the current exhibition. I loved the Dzubas exhibition and left with a beautiful exhibition catalogue. Dzubas was championed by Greenberg, was acquainted with Pollock, de Kooning, Kline, et al., and was a member of The Club. He even shared a studio with Frankenthaler at one point. So, why haven’t I heard of him till now? I’m sure I’ve read about him, but for some reason, the name didn’t stick. In any case, I was glad to experience this exhibition, full of large-scale works with stacks and patches of acrylic color, each with a fuzzy, hazy edge that at once distinguished it and associated it with its neighbor. Turns out that that Dzubas was primarily influenced by Tiepolo’s frescoes. I found the use of color oddly idiosyncratic and full of juxtapositions of high color and rather muddy, earthy tones. My favorite piece was the epic Procession, from 1975. This work spans nearly 300 inches and is a true tour de force.

Dzubas made small studies for these works, which seem at odds with the grand presence of the paintings, which feel very spontaneous and in the moment. In fact, most of the large works in the exhibition were accompanied by their studies. I’m not sure if it helps or hurts the overall experience of viewing this show. Rather than studies, they almost feel like after-the-fact miniatures of these epic paintings.

Procession, 1975, Magna on canvas, 116 x 294 inches

Gotta love the Dymo label on the side of the frame!

In a Yares Art side gallery, I encountered this lovely Kenneth Noland painting, Spring Call, 1961, as well as Morris Louis’ Number 9, also from 1961.

After leaving Yares Art, I had a quick bite and then took the subway down to the Lower East Side.

John Zurier: North from Here, Peter Blum Gallery, through November 9

Of course, I know John Zurier from my old life in San Francisco. I greatly enjoyed John’s exhibition, full of wonderful color, subtle brushwork and the introduction (or perhaps just a bit more emphasis on) edges and structure within the fields of color. I’m always interested in observing John’s choice of canvas/linen, which varies from work to work. Sometimes he uses a fine, tight weave, while other times he employs a very nubbly, almost burlap-like weave. These works really honor the edge of the plane, and seem to take compositional cues from the underlying structure of the stretcher bars.

My favorite piece in the exhibition: Hundasúra, 2019, oil on linen 18 x 22 inches.

I wanted to see more galleries on the LES, but I still had a lot on my list, so I Ubered over to Chelsea.

Ed Clark: Paintings 2000-2103, Hauser & Wirth (Chelsea), through October 26

Ed Clark’s paintings remind me a bit of super-sized Howard Hodgkins, albeit with a completely different palette. These works are made using a technique that Clark refers to as “the big sweep”— literally, using a push broom to apply paint to canvas. The scale of the “brushwork” (okay, let’s call it “broomwork”) is epic. There’s no other way one could make these marks and gestures. Clark, a native of New Orleans, spent many years in Paris, hanging out with American expat painters such Joan Mitchell and Sam Francis, as well as a generation of important African-American artists who’d fled racial discrimination in the U.S.

Amy Sherald: the heart of the matter, Hauser & Wirth (Chelsea), through October 26

Amy Sherald’s exhibition was all but mobbed. She’s enjoying a moment, deservedly, after acing the Michelle Obama portrait commission. However, I feel something is missing in the discourse around her work. While issues of race and representation are at the forefront—as they are in the broader culture—they are not what make these paintings successful works of art. What makes these paintings successful is her subject matter combined, crucially, with they way they are painted. Sherald’s achievement is not merely her contribution to our contemporary discourse about race. It’s her contribution to painting, in terms of stylistic leanings and formal decision-making.

In preparation for this writing, I ran across a conversation between Sherald and Osman Can Yerebakan. They covered many topics, including tidbits about Sherald’s partner, her dog, her move from Baltimore to New Jersey, single-hood, romance, her Southern identity…in essence, just about everything but painting, which I found quite curious. However, there were two little factoids to savor: 1) Sherald studied with Odd Nerdrum in Norway, and 2) She buys clothes with which to style her models. The former is so, well, odd, that I don’t even know what to make of it. The latter really piqued my interest, because one of the things I admire so much about Sherald’s works is the way that she uses clothing to construct her compositions, and to signify other value systems that may not be so readily apparent. For example, when I look at the Obama portrait, in addition to Sherald’s stated references to Mondrian and Gee’s Bend quilters, I am reminded of Michelangelo’s Pieta and it’s pyramidal structure, so typical of Renaissance art.

I’m eager to see how Sherald will continue to push the boundaries. This exhibition includes two very large works, one with four figures. However, this is the one that sticks with me. Sherald has a knack for posing her subjects’ limbs in a way that is rather uncanny and strange. It might be my imagination, but I’ve always thought that Michelle Obama’s left arm is rendered in a way that makes it appear bit long. If so, it’s a mannerist tweak that adds yet another layer of art historical references and compositional interest. Similarly, the subject in the portrait below has a strange left arm, with the hand not visibly in a pocket, but awkwardly held behind her back at a strange angle. This lends a bit of tension to the otherwise straightforward, frontal composition. I love this detail, as well as the patterned dress, which harks back to Pop Art (references to Wonder Bread, and/or the game Twister) and also to Op Art strategies.

Luckily I had the forethought to pick up the heavy card for this show at H&W’s Uptown space. In the Chelsea gallery, viewers were frantically trying to grab keepsakes.

Sarah Sze, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, through October 19

Once again, Sarah Sze creates an exhibition out of anything and everything at hand. The centerpiece of this show, a fragile, scaffold-like structure with scraps of paper and even containers of water serving as screens for tiny video projections, was very similar to an installation I saw in Munich a couple of years ago, In this case, though, Sze uses every inch of the gallery as a studio, laboratory and exhibition space, including the front of the building and various administrative spaces. A backroom serves as a studio space in chaotic disarray, as if the artist had just stepped out for a coffee. Upstairs, there are several paintings that function like accurate 2-D depictions of Sze’s layered, hyper-speed, ad hoc installations. They make sense in a way, and are fully in keeping with Sze’s oeuvre, but I was distracted by their fragile surfaces, with bits of collaged paper tacked on. Although the press release states that Sze was “originally trained as a painter,” let’s face it: that was a lifetime ago. Sze has consistently invested her energy elsewhere, and this exhibition made me think that she has overstretched a bit. To me, the installations incorporating light, video, sound, structure and detritus are still the most interesting and compelling works Sze has created thus far.

Anni Albers, David Zwirner (Chelsea), through October 19

What can I say? This show is both ravishing and rational. It’s logically and materially satisfying, and optically and tactilely engaging. Some of the works show signs of wear and tear, which only serves to make them appear more precious and appealing. I could’ve spent hours here, were it not for all of the mid-century-modern-loving hipsters parading around.

Gorgeous large-scale piece, Camino Real, 1968.

A little threadbare in spots, but very commanding.

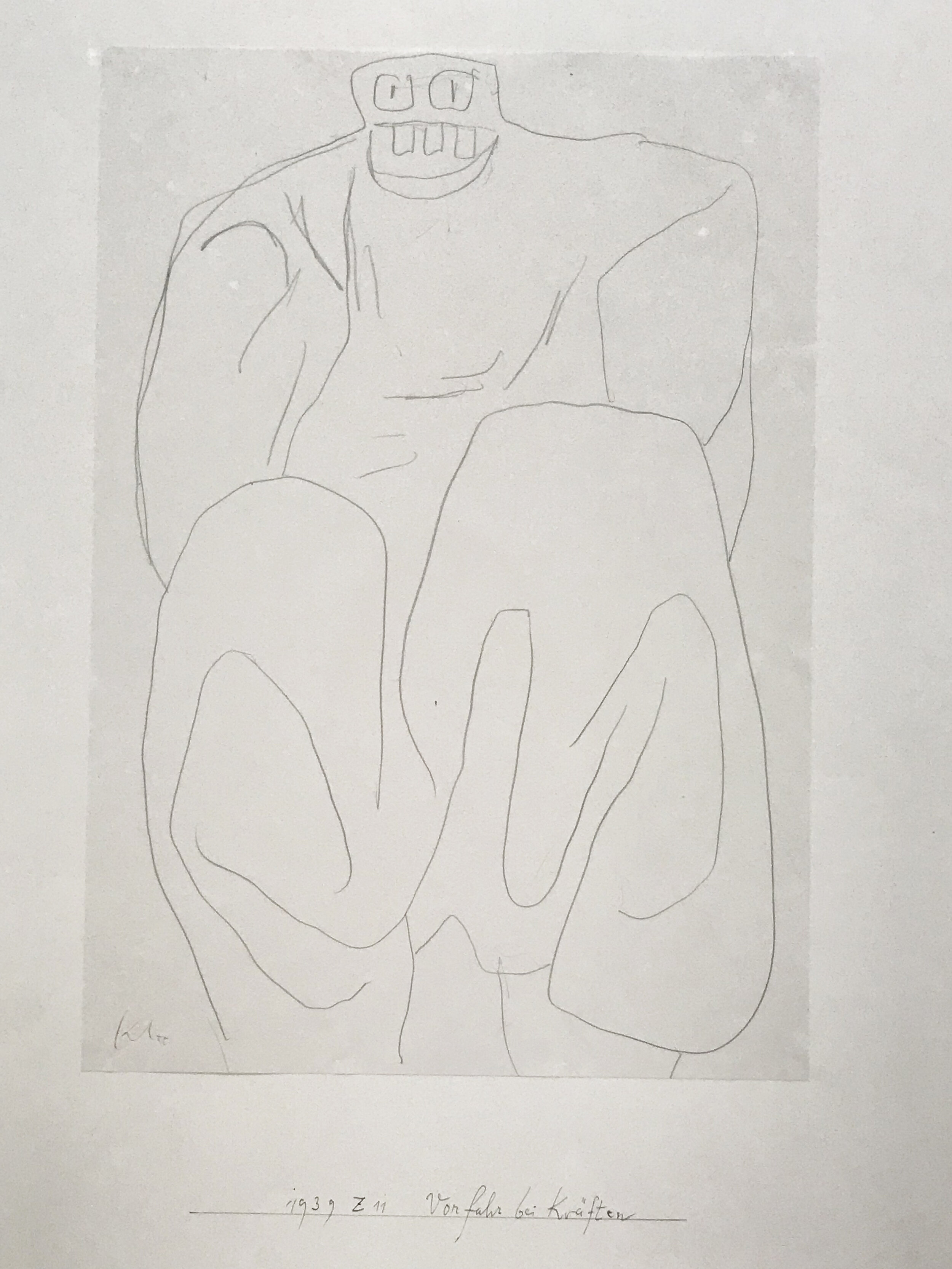

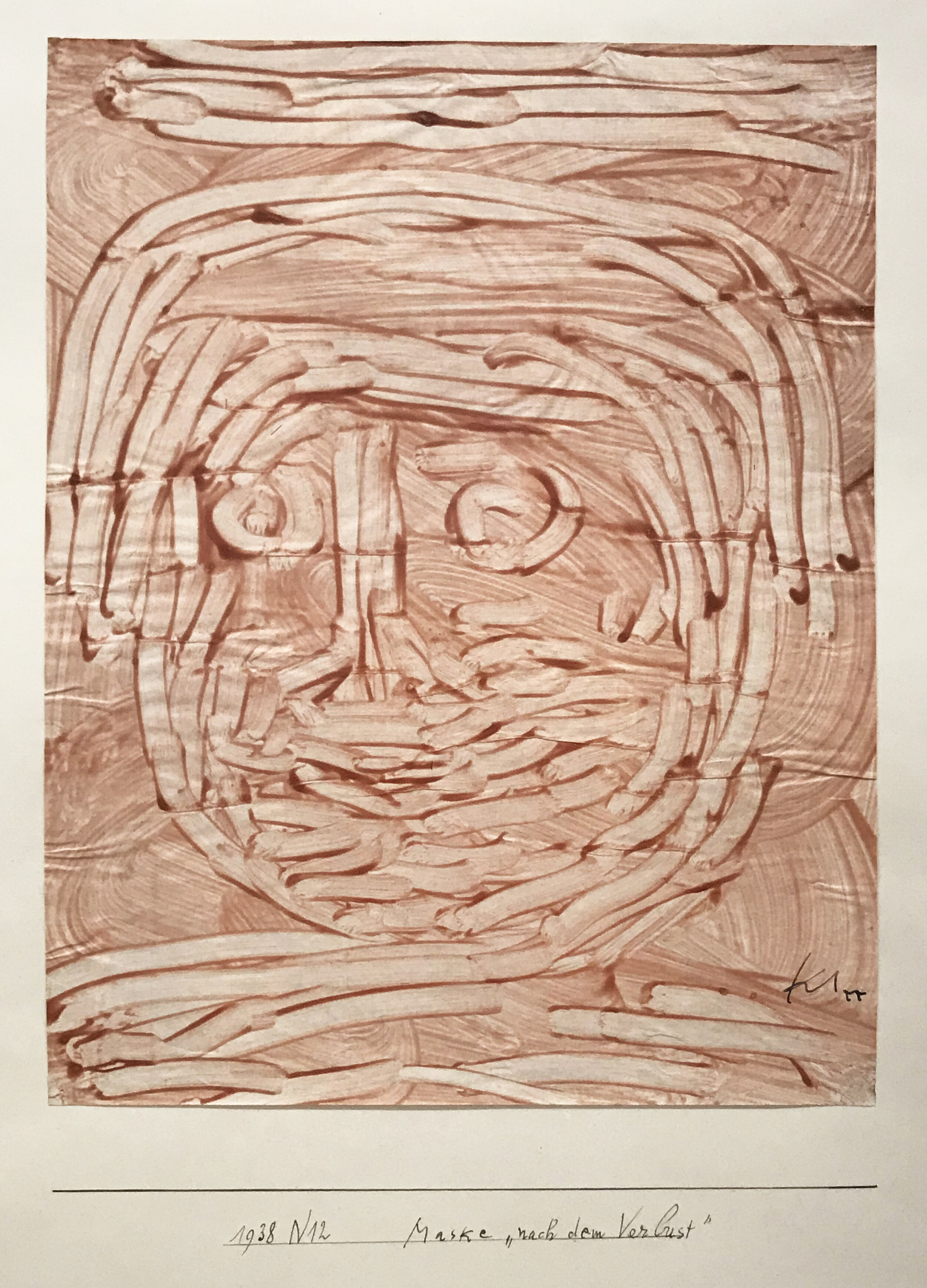

Paul Klee: 1939, David Zwirner (Chelsea), though October 26

This exhibition is truly spectacular. The title says it all: 1939. According to the press release:

“The exhibition focuses on Klee’s art from 1939, the year before he passed away, which marked one of the artist’s most prolific periods.

Toward the end of 1933, in response to the suppression of avant-garde art practices by the newly empowered Nazi party, Klee left Germany, where he had primarily lived since 1906, and returned to his native city of Bern, Switzerland, residing there for the remainder of his life. From 1935 until he passed away, in 1940, Klee continually struggled with illness, which at times impacted his ability to work. Yet, in 1939, against the backdrop of immense sociopolitical turmoil and the outbreak of war, Klee worked with a vigor and inventiveness that rivaled even the most productive periods from his youth. The works on view illustrate how Klee responded to his personal difficulties and the broader social realities of the time through imagery that is at turns political, solemn, playful, humorous, and poetic. Ranging in subject matter, the works all testify to Klee’s restless drive to experiment with his forms and materials, which include adhesive, grease, oil, chalk, and watercolor, among others, resulting in surfaces that are not only visually striking, but also highly tactile and original. The novelty and ingenuity of Klee’s late works informed the art of the generation of artists that emerged after World War II, and they continue to hold relevance and allure for artists and viewers alike today.”

The works on view, most very intimate in scale, are by turns delightful and ominous. I was obsessed with Klee when I was a teenager, but lost interest somewhere along the way. Well, I once again count myself among Klee worshippers.

Monsters in Readiness

Ancestor in full vigor

Mask “after the loss”

Nordic artist

Ray Parker: Simple Paintings c. 1960, Washburn Gallery, through November 2

This was my first visit to Washburn’s new space in Chelsea. Washburn, Peter Blum Gallery and a few others were displaced from their Uptown digs in 2017. After 25 years at three locations on 57th Street, the gallery now occupies a modest, street-level gallery in Chelsea. It felt a bit odd to duck in, fresh off the sidewalk, but the minute I opened the door, Ray Parker’s paintings walloped me. What a delight, after the relatively somber (and extensive) Albers and Klee exhibitions. These paintings, with their large, soft-edged, blobby forms (mostly in pairs or trios) occupy the odd space between Abstract Expressionism (Motherwell, Gottlieb) and the crisper geometries and higher color of Color Field painting. The forms have a bodily presence, almost like brightly colored sleeping bags on a neutral ground.

Bernard Piffaretti, Lisson Gallery (Chelsea), through October 19

Last but not least, I straggled over to Lisson Gallery. I loved this super fun, fresh exhibition. Piffaretti has employed his technique of dividing the painting surface and doubling his images for over 30 years, highlighting sameness and difference and questioning notions of originality. He does not exactly “copy” the left side of the painting; rather, he recreates and re-executes the same colors and movements of his hand and brush. Perfect Po-Mo paintings.

Finally, parched and tired, I stumbled back onto the sunny street and hoofed it back to my hotel, before heading Uptown for dinner.

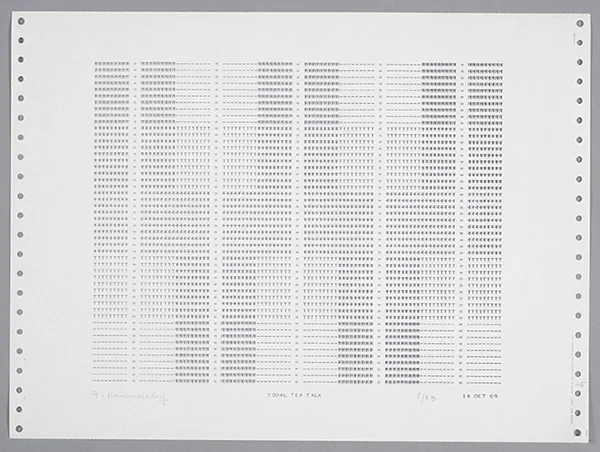

In autumn 2016, I made my first trip to Magnolia Editions in Oakland, CA for the stated purpose of "seeing what's possible," at one of the Bay Area's most respected and innovative printmaking and fabrication studios. As it turns out, just about anything is possible at Magnolia!

First, a bit of background. Of course, most everyone in the Bay Area is familiar with Magnolia, and working with the team was a long held dream of mine. Till now, I had very little printmaking experience, and I confess that I barely knew the difference between an etching and a relief print. But, as it so happens, Nicholas Price is one of Magnolia's master printers. I've known Nicholas for several years, through our mutual involvement with Root Division, a local non-profit arts organization. Nicholas mentioned to me that Magnolia might be interested in inviting me to do a project. Of course, I was intrigued, but with deadlines stacked up at the time, I felt I had a bit too much on my plate. When the dust finally cleared, about a year later, I'd had a good long time to do a bit of subconscious work on ideas for a project. I wonder, artist friends, if you work in this way? I sometimes feel I have two levels in my brain. It's as if that symbolic "back burner" is real. Ideas are simmering, with just an occasional stirring every now and then. Anyway, when I finally sat down to work on some preliminary sketches, they jumped out of my laptop in full form. I sent them over to Nicholas and thus the project commenced.

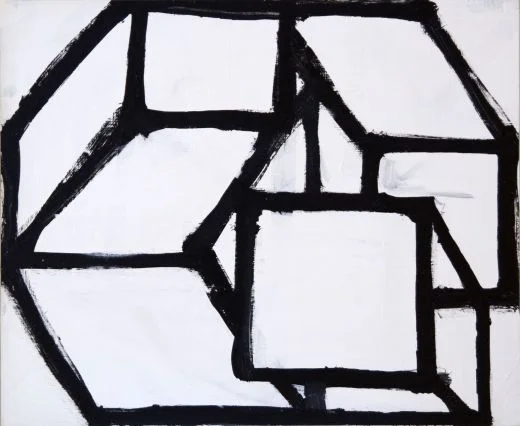

What follows is a photo journal, from the beginning of the process to the end. I took loads of photos on each of my visits to Magnolia, ever fascinated by the very complex process of making the prints. The project, Identical/Variation (green, red, blue, black), is a suite of four prints, each comprising an etching in black ink; elements of vibrant UV acrylic ink; and a woodblock relief, printed in four different colors in variable orientation. Like the Identical/Variation theme that I have revisited over the years in my paintings, Identical/Variation (green, red, blue, black) employs a variable matrix that allows for the possibility of originality within the parameters of repetition.

Magnolia has been in the same building for a very long time. It's a privilege just to hang out in their studio. Every nook is perfectly attuned to purpose and task. I love seeing how other people organize their studios, and I took mental notes on Magnolia's organization and flow. It's orderly, but well lived-in, and flexible enough to be fluid and a bit funky. Don and Era, artists and proprietors, are ever-present. Don, like a brilliant mad scientist, was deeply engaged in learning how to duplicate the minute fibers and texture of Renaissance paper during the months that my project took to complete, while Era serenely presided over other projects, as well as the business end of things. On any given day, artists flow in and out, working on their projects, the phone rings, and people pop in for tours of the studio. All the while, master printers Nicholas Price and Tallulah Terryll calmly and expertly do the meticulous work of making prints and other works of art.

Magnolia is known for combining traditional and digital techniques. We determined that the first step would be an etching, derived from my digital file, and printed (in the negative) onto the etching plate, in a series of 8 steps, each with a longer duration in the acid bath. In the foreground, you can see the negative of the design for my etching plate, and in the background, the big flatbed printer. Tallulah is the master of this beast!

Printing the etching plate on the flatbed printer.

Here, you can see how the acid has burned lines into the copper plate. Since we printed and etched multiple times, some lines are deeper than others, resulting in lovely line variety in the print.

The copper plate on the flatbed printer, awaiting another layer of black acrylic ink. The acrylic ink resists the acid, and will later be cleaned off.

This is the plate after the final pass of ink and the final acid bath. Each time, the ink covers more of the image. The exposed areas are etched with acid multiple times, resulting in deeper lines that will eventually hold more ink.

The copper plate is shiny as a new penny, until Nicholas begins spreading ink onto the surface. Every little incised line must be filled.

After the plate is inked, the excess ink is wiped off. This takes time. A lot of time! The ink must sit only in the etched line, while the rest must be removed.

The plate, inked and wiped. Now it is ready to print! The paper is slightly damp, and wrapped in plastic so that it won't dry out. Magnolia has a special drying room for the etchings. Ideally, they will all dry and shrink at the same rate. Since my prints have multiple steps, registration was an issue. The shrink rate had to be carefully calculated and monitored, so that subsequent steps will register with the etching.

Very precise instructions on the printing press!

Further precision in the placing of the plate on the press. Each of these steps must be checked and double-checked.

Wow! Our first glimpse of the etching! Pulling the print is very exciting. There is so much labor and methodical process in printmaking. Seeing the print for the first time is like opening a gift!

One reason I am so excited about this project: printmaking allows for such extreme complexity and detail.

This is what blew me away: the etching is hard and soft at once, with an abundance of line variation, somewhat similar to a hand-drawn pencil line, but in rich, deep black. This is due to Tallulah's decision to do 8 passes with the printer and 8 successively longer acid baths. It really paid off!

Once we felt good about the etching (although it would take weeks for Nicholas to print enough for the edition) we were able to move on to the next step: the UV acrylic ink. Tallulah once again masterminded the flatbed printer, getting the registration just right and adjusting each color.

In my original file, the colors were very loosely placed, as you see here. They align to the shapes, but I wanted them to have a looser, almost hand-painted feel.

Once we figured out the acrylic printing, it was time to prepare for the final step: the woodblock relief print. We decided to laser-etch the block. I have always wanted to do woodblock printing, and it's great to have the option of using digital technology to cut the block. Although I love the idea of carving the block by hand, in this case, I wanted to preserve the pixilation and precise detail of my image.

The block, before inking.

I love the detail we were able to achieve with the laser.

Once the woodblock was cut, Nicholas and Tallulah worked on building up a number of prints, complete with the etching and the acrylic printing, in preparation for printing the whole edition of Identical/Variation (green), the first color in the series.

Of the four colors in the group, the green was the most difficult to mix. I wanted it to be relatively opaque, and was amazed to see how different in character ink is from, say, oil paint. It is so saturated, even when transparent.

Even the task of applying the ink to the roller takes a lot of patience. We remixed the green perhaps 6 or 7 times. Each time, Nicholas had to thoroughly clean the palette and the roller before testing the adjusted color.

If you want to build big muscles, become a printmaker! The large roller is quite cumbersome and heavy.

Rolling the ink onto the block. It is very tricky to get just the right amount of ink on the block, with even coverage over the entire surface. Nicholas showed me that the goal is to achieve an 'orange peel' texture with the ink. Assessing the ink requires attention not only to the appearance of the ink on block, but also to how the ink sounds as it is being rolled and how it feels.

Perfect coverage. Ready to print!

Testing the green alone, without the etching and inkjet steps.

Testing the green woodblock.

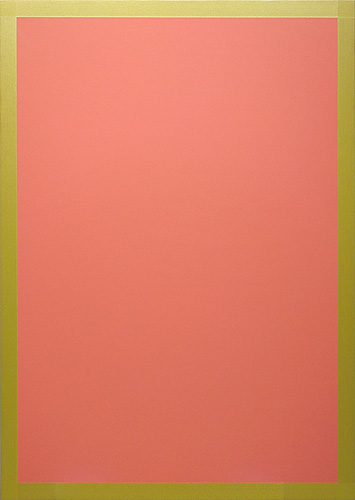

A detail of one of the early test prints. There is a lot of variation in the surface, due to how the ink sits on the first two elements.

The color that we finally settled on!

Are printmakers the only people who still use phonebooks?

Pulling the green print.

Once we finalized the green, we moved on to the red. We nailed the color quickly this time around.

A detail of the red test print. Even though the ink sits on top of the first two steps, it seems to fall back in the red print, as if it's in the background.

Delicious reds!

Pulling red.

A striated view of the press, the woodblock and the print.

Rolling blue. Like the red, we had a relatively easy time mixing the blue ink.

A shot of the block with the blue ink applied. It had a metallic sheen to it.

To check the colors, Nicholas would draw them down on raw paper with a mixing knife. However, the quality of the ink is different when it is printed, due to the way the ink is rolled on the block and the pressure that the press creates.

Drawing down the black ink on a test print.

Transparent base. We mixed this into our colors to create more transparency in the ink. I was amazed by the high color saturation, even when mixed down with the transparent base.

What do you do with rejected prints? Make buttons! Magnolia has a button making machine, so I spent a few hours cutting circles out of some of the rejected prints, which I then mounted onto metal button forms.

Last but not least: the black print. Again, the ink looks almost metallic on the block. You can clearly see the orange peel texture of the ink.

Pulling the black print. With this, we neared the end of the project, at least in terms of the major esthetic decisions. Our next task was to curate the prints, going through each color methodically to determine which made the cut for the edition, the printers' proofs and the artist proofs. I also signed and numbered the prints, after Nicholas and Tallulah applied Magnolia's chop and my chop. I felt surprisingly anxious about signing the prints. Even though the paper is very sturdy and tough (it has to be, considering how much it is handled) it is very hard to cleanly erase pencil lines.

Identical/Variation (green)

Identical/Variation (red)

Identical/Variation (blue)

Identical/Variation (black)

I am so grateful to Magnolia Editions for the invitation to work on this project. The generosity of Don, Era, Nicholas and Tallulah, along with the fantastic vibe of the studio, the other artists who flowed in and out, and even the neighborhood (with other artist-run businesses in close proximity) made for a dynamic environment in which to collaborate.

One of my favorite things is to travel to see art. As you know, I've half-jokingly described myself as an Art Ninja: I feel I'm wearing x-ray goggles, and my mind and heart race as I weave through museum crowds like a wisp of a shadow. Travel, getting out of one's world and away from one's cares and duties, frees up the mind. Art viewing skills are heightened and I have the capacity to clock more museum time. Thankfully, my patient spouse is game for my relentless and (let's face it) greedy approach to museum-going. But, how much of it sticks? I mean, really sticks? I like to fully immerse myself, see and read as much as possible, take notes and photos, and then sit down a few weeks (or months) later to recall the few works, of the thousands that I may have seen during a trip, that have permanently adhered to my brain cells. My beloved and I recently spent two weeks in Munich, Salzburg and Vienna, and I'm still sorting through museum ticket stubs, catalogues and books, hundreds of photos and a notebook filled with my decidedly unattractive scrawl. But, here are a few things (in no particular order) that I'm still thinking about and continue to see, as afterimages.

There are a number of treasures at the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, including several terrific van Goghs, a moody Gauguin, a decent Monet and an interesting Bonnard, but this Manet really knocked my socks off. The first thing that popped into my mind was, "That black! Manet's black! Boy, I would love to be a fly on the wall, listening to Manet and Kerry James Marshall discussing the color black!" In this case, the young man's black jacket takes hold of your eyeballs and doesn't let go. It's a bit shocking, really, in a purely retinal/optical sense. And then...the eyes begin to take in the scene. What's going on here? The space has a strange push/pull, like a wheezing accordion, opening and closing in only the midrange. The oysters and the lemon...oh, the lemon peel! So tantalizingly tangible, just falling off the edge of the table. The young man, one Leon Leenhoff-Koella, seems plucked from another scene, and pasted onto this one. He was allegedly the younger brother of Manet's wife, Suzanne Leenhoff, but was possibly her son, maybe from a relationship with Manet prior to their marriage. Thus, the woman in the painting might be his mother, and the man might be Manet, who might be the young man's father. However, scholars seem to disagree about this, and of course we will probably never know the truth. To the left is a pile of weapons and armor, in relatively sharp focus. I thought, "This young man is in a toxic family and he's aiming to get the hell out of Dodge." A fantastic painting, in true Manet-mystery fashion. Apparently, I'm not the only one seduced by the black jacket. I found this quote on www.manet.org: "Henri Matisse saw Lunch in the Studio in 1910, and was so struck by it that thirty-six years later he could bring details of the work to mind: 'The Orientals used black as a colour, particularly the Japanese in their prints. Closer to us, there is a certain painting by Manet, I remember the black velvet jacket of the young man with the straw hat is in downright black and light.'"

I was delighted to stumble across this gem, part of the The Michael and Eleonore Stoffel Foundation at the Pinakothek der Moderne, in Munich. In general, I respond to Kelley's works as I would to an old friend kicking me in the gut: a mixture of surprise, pain, anger and sadness. But, wait! Back up! Before the gut punch: a brief, naive moment of pleasure and joy, even. Pleasure, in response to the formal qualities of the work. Joy, in the feeling of recognition: I know this. Case in point: a patchwork of 70s & 80s wool sweaters, with a carefully arranged assortment of panels, some merely blocks of solids and stripes, some displaying vintage graphic logos of ski resorts. For a moment, I was lost in a reverie, thinking of guys and girls with feathered hair, wearing Levis and brightly colored ski jackets, hot-dogging on the slopes. But... oh, wait, what's that? An oddly-proportioned dummy’s torso, adorned in a sweater of similar patches. But in this case they are arranged like so many colorful bricks, and sewn together with very prominent, thick stitches (think Frankenstein's monster). Suddenly: an intense wave of sadness for the outsiders (Yes, me. Yes, us.) living in a world of insiders.

Beckmann painted nine large triptychs in the 30s, following his dismissal from his position at the Frankfurt School of Art in 1933 (after which he fled to the Netherlands for a self-imposed exile from Nazi Germany). I think I've seen three of them. I felt a chill down my spine when I turned a corner in the Pinakothek der Moderne and into a gallery containing several Beckmanns. Seeing them in Munich felt different than seeing them elsewhere. The vivid, relentlessly violent imagery, the compact compositions and the high color are an unequivocal indictment of human cruelty. Legs and arms are torqued into impossible positions, compositions are compressed and claustrophobic and the graphic use of black (and the triptych format) harken to medieval art. The reds and blacks and nickel yellows are thrilling, but they're just a smidge away from being nauseating. I stared at this painting for a very long time. The only other people in the gallery were the guard and a very old German man who brought one of the portable museum stools into the room. He sat. I stood. We stared in silence.

Well, this was a surprise! We spent a couple of days in postcard-picture-perfect Salzburg, in the historic city center, amidst its Christmas markets, castles, churches, fanciful shops and incredible views of snow-capped mountains. We popped into the Museum der Moderne's Rupertinum (the old town location; the main museum is situated high above the rooftops of on Salzburg's Mönchsberg). The Rupertinum is a small baroque building in the heart of the old town. We were delighted by the Art & Politics exhibition. An excerpt from Curator Stefanie Grünangerl, Librarian Museum der Moderne Salzburg:

"This exhibition showcases works from the museum’s collections that articulate pointed views and solicit debate on issues in society and politics. Such socially critical art is especially apt to illustrate the value of a collection of prints and other “ephemeral” media that allow for comparatively inexpensive reproduction and dissemination such as flyers, posters, postcards, stickers, and magazines. Politically “engaged” artists do not primarily make work so that others contemplate it with a view to its aesthetic merits; they rather want to broadcast concrete messages. Yet they also reflect on the constraints that circumscribe their scope of action and the limitations of art and political activism in general."

I confess: sometimes my eyes glaze over when viewing a show like this. I mean, it's not exactly a visual feast. And yet, this little exhibition, very text-heavy, minimal and (at first glance) rather dry-looking, was the perfect antidote to the formidable cuteness of Salzburg. There, in long, plexiglass vitrine tables, were countless gems, but this is the one I'll always remember. From the accompanying text:

"This first-person narrator of a postcard by Martha Rosler would seem to recount trivialities, yet there are subtle but unmistakable political overtones, raising questions of economics and labor. The missive is a prelude to several novels in the form of postcard series...in which Rosler examines the linkages between food, imperialism and exploitation as well as resistant practices."

This piece, so juicy, so dense with layers of meaning, its fragmented thoughts so provocative, absolutely captivated me. The awkward yet pointed phrasing, the balance between what is suggested but not elaborated upon, the contradictions of meaning...I fantasized for a moment that I was back in grad school at CalArts, deconstructing and parsing out meaning for hours, in a windowless room, thick with cigarette smoke under horrid florescent light. I find this small, discolored postcard to be a poetic call to arms.

The Haus der Kunst had not one, not two, but THREE excellent exhibitions on view: Sarah Sze, Centrifuge; Thomas Struth, Figure Ground; and Frank Bowling, Mappa Mundi. Also on view: Oscar Murillo's Going Forth-The Institute of Reconciliation, Polina Kanis' The Procedure and Mel Bochner's The Joys of Yiddish (A small encyclopedia).

First, a bit of history. From the museum's website:

"After its opening in 1937 as "Haus der Deutschen Kunst” [House of German Art], the Neoclassical building served to demonstrate National Socialist cultural politics and became the party's leading art institution. After the end of World War II, the museum building was first used by the US army as an officer's club. Art exhibitions took place as early as 1946. The return of modernism to the very place where the denigration of artists had begun served as part of a larger historical contemplation.

Haus der Kunst became an important venue for featuring avant-garde works - like Picasso's Guernica in 1955 - and thus a counterbalance to its defamatory stance during the Third Reich. Since then, Haus der Kunst has been transformed radically into an international center of modern art exhibitions, and, today into a global museum of contemporary art. The cultural examination and curatorial analysis of this process has become an ongoing, integral part of Haus der Kunst's program."

The Director of the Haus der Kunst is none other than Okwui Enwezor, former Dean of Academic Affairs and Senior Vice President (from 2005 to 2009) at the San Francisco Art Institute , where I taught in the undergraduate and graduate programs for 11 years.

As if all of this history weren't enough to pique one's interest, the building itself is quite astonishing in both scale and fascistic demeanor. The vast, cavernous spaces have been adapted into serviceable galleries that would likely swallow more intimate or subtle exhibitions. However, the shows on view were all capable of holding the space.

Sarah Sze's Centrifuge is positioned in the main gallery on the ground floor. The space is enormous, dark and downright intimidating. I was drawn in by the piece, an impossibly fragile structure of reed-thin supports, fashioned into a fantastical, stadium-like form that serves to display fragments of paper, many of which serve as projection surfaces. The projections and sound elements extend into the far reaches of the cavernous space. As is typical for Sze, the piece employs a range of detritus, presumably scavenged on site: office supplies, trash, coffee cups and the like. This fragile arrangement somehow humanized the cold, forbidding gallery, with delightfully fanciful, unexpected detail and delicacy.

According to Sze: Centrifuge’s “interior sculpture will seem caught in an indeterminable state between growth and decay. As the visitor approaches the sculpture it will immerse them in a micro scale at its interior, while simultaneously gesturing to a macro scale as it projects into the larger space of the hall. The sculpture will function both as a site of action, as well as a projector, illuminating the ceiling and giving the space the openness of a palazzo or city square.”

For me, the sum of this piece is much greater than Sze's description.

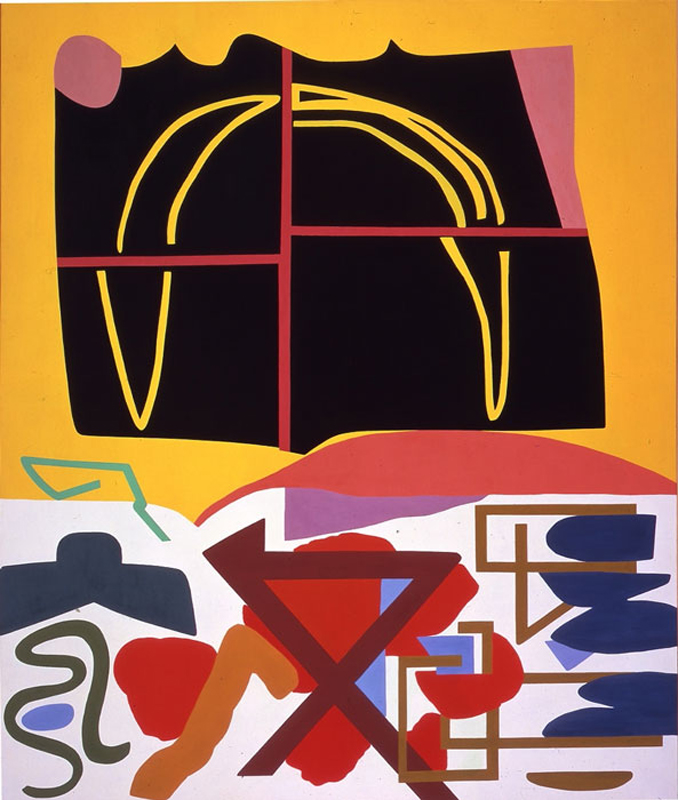

Frank Bowling's Mappa Mundi was a revelation to me. I am sorry to admit that I was unfamiliar with Bowling till now. According to the museum's website:

"Frank Bowling: Mappa Mundi presents a comprehensive overview of rare and never-before exhibited large-scale paintings along with other works by the Guyanese-born British painter Frank Bowling. Born in Bartica, British Guyana, in 1934, Bowling left his native country at the age of nineteen, arriving in London in 1953 as part of the momentous wave of Anglophone West Indian and Caribbean populations who migrated to England in the aftermath of World War II. Later he would study painting at The Slade School, University College London, and the Royal College of Art, distinguishing himself with the silver medal for painting (David Hockney received the gold medal) in RCA's 1962 graduating class.

The principal anchor of this exhibition is the monumental and celebrated "map paintings" (1967–1971) that were first shown to acclaim at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1971. For Bowling, whose art is preoccupied with place and history, like those of his Caribbean contemporaries, the poet Derek Walcott and philosopher Edouard Glissant, the use of maps as conceptual objects of painting make for a fitting transactional trope through which to tackle the idea of geography and narrative. Maps and mapping present not only an exploratory metaphor through which to mirror the physical weight of painting; they also project absorbing, metaphysical and protean domains."

I was blown away by this exhibition. The map paintings, in particular, are gorgeous--especially those employing fiery yellows and hot pinks. The color and surface qualities are compelling, the progression of thought and action is convincing and the show was perfectly installed. The wall text was informative and direct and the exhibition included the artist's archive, which would more than suffice on its own as a fascinating exhibition. It was pure joy to be surrounded by and immersed in this terrific, accomplished body of work, with only the occasional gallery guard disrupting the view. What a treat! The catalogue for this exhibition is at the top of my post-travel wishlist.

Haus der Kunst describes Thomas Struth's Figure Ground as:

"... a comprehensive survey of his genre-defining oeuvre. Covering four decades of work and every phase of his career, the exhibition focuses on Struth's social interests, which represent the important forces of his influential artistic development. Comprised of more than 130 works, this exhibition is the largest survey of his artistic career to date. It brings together never-before-shown early works and collected research material drawn from his archive; these, elucidate the far-reaching and long-standing ideas behind the works and demonstrate the process of his artistic translation up to the perfection of the image."

The exhibition was so huge that I kept losing my Beloved in the massive gallery spaces, which seemed to go on forever. Some bodies of work appealed to me than others. My favorite is the recent series "Nature & Politics," in which Struth documents technological environments of the aerospace, energy and medical industries. I had recently seen one of these enormous prints in a collector's home in San Francisco and had been astounded by the visceral, writhing quality of the extreme-focus details. These sterile spaces (research labs, space vehicles, energy facilities) are almost too much to take in, with their harsh, cold light, miles of cables and wires, and vastly complex conglomerations of engineered metallic and plastic forms. Though the human figure is absent, these environments nonetheless imply the presence of the human body and its frailties, through the technology required to sustain it, transport it and study it.

We had to look high and low to find this little lady, in Vienna's Naturhistorisches Museum. First, I confess that I was surprised to find Venus in a natural history museum...in my mind, she resides in the first chapter of Janson's History of Art. We were in the museum on the one night of the week that it is open until 9 PM (all the better for packing in four museums in one grueling day). We tromped, in reverse order, through the hierarchy of biological classification, beginning with the primates and ending with microscopic life forms. On and on we went, through rooms of massive wood and glass cases full of taxidermy and specimens in jars, flesh and feathers faded to a dull grey-brown. Perhaps it was because we were alone in the quiet, stately galleries, without huge groups of squealing school kids, or perhaps I'd just hit a wall after 10 hours in museums, but I was overcome with sadness. I couldn't look at the elephants or lions. My heart broke when I saw case after case of birds, and then butterflies, the latter being the only creatures who still sported flashes of color. Oh, the loss of animal life over the years, the spoils of human destruction, corridors filled with extinct and near-extinct creatures encapsulated and displayed in eternal stillness. Once, I would've said that I love natural history museums. But now, I'm not so sure. We pressed on, through the gems, the splendid meteor collection and the prehistoric art. Finally, we found our Venus, in a special side gallery--basically, a black tomb--in the dark, lit by a dramatic spotlight. She's small, but mighty. Faceless, anonymous, a symbol...a vessel. My beloved said, "She is the grim little seed of the Patriarchy. Her humanity is amputated. She has no arms, no feet, no agency, no personhood. Her head is encased in a basket. Things haven't changed much in 30,000 years."

I thought of the Commodores song, Brick House:

"Ow, she's a brick house

She's mighty-mighty, just lettin' it all hang out

She's a brick house

That lady's stacked and that's a fact

Ain't holding nothing back"

Harrumph.

The Kunsthistorisches Museum is a world class museum, on par with the Louvre, the Uffizi Gallery, the Met, and the like--the grand museums of the world that specialize in old master paintings and antiquities. The museum building is a veritable mirror image of the Naturhistorisches Museum, and the two face each other across Maria-Theresien-Platz. The Kunsthistorisches is literally packed with treasures. My head was spinning, trying to take in the abundance of first-rate works by Rembrandt, Bruegel, Vermeer, Raphael, Velázquez, Dürer, Holbein, et. al. I often find myself tallying masterworks when I'm in museums such as this. "Okay, there are 35 or 36 Vermeers in the world, and now I've seen 19 of them." I'm not advocating this, and in fact it's probably a bad habit, but I can't help it, especially when I am surround by masterpieces so old and so rare. So much art, so little time. But, hey, it's not as if I'm tallying Warhols.

It's tough to pick a favorite, or even a handful of favorites, due to the general level of excellence reflected in the collection. One thing that stuck me: we saw a lot of paintings of decapitated men. I mean, a lot. A good number of depictions of Judith and Holofernes, Salome with the head of John the Baptist, and a very interesting Caravaggio, David with the Head of Goliath. Perhaps they just happened to be hanging in close proximity, but the quantity seemed somewhat remarkable. Of course, old master depictions of women holding the heads of decapitated men has always provided a bit of relief from Jesus' suffering, Mary's placid steadiness and relentlessly chubby, rosy putti. The triumph of the bloodied, disembodied head represents the feminist impulse within the unforgiving symbolic world and general misogyny of Christianity. So, here are two of my favorites, each of which displays a pretty astonishing level of symbolic gender-bending.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, Judith with the Head of Holofernes, c. 1530

(The sword! The hands!)

Caravaggio, David with the Head of Goliath, c. 1607

(Um, what's with his shirt, pants and the opening of his shoulder bag?)

Confession: I now count myself among the legion of Gustav Klimt fans. Don't get me wrong, I never really disliked his work. If you spend time in Vienna, you will be immersed in Klimt. You'll find his work at the Belvedere and the Leopold, as well as Secession, which houses the Beethoven Frieze. We saw a lot of Klimt paintings, including Death and Life (1910/1915), Judith and the Head of Holofernes (1901), The Kiss (1907-08), all of which are pretty spectacular. However, the piece that will remain burned into memory is the Beethoven Frieze. According to Secession's website:

"Gustav Klimt created the famous Beethoven Frieze for the XIVth exhibition of the Association of Visual Artists Vienna Secession, which was held between April 15 and June 27, 1902. Conceived as a tribute to the composer Ludwig van Beethoven, the presentation epitomized the Secessionists’ vision of an encompassing synthesis of the arts."

After the exhibition, the frieze was cut into sections (overall, the piece is 7' h. and 112' w., with the plaster panels weighing in at about four tons) and stored for decades, both before and after being confiscated in 1938 from the dispossessed August Lederer who bought it in 1915. It is a sordid story, but not an uncommon one. It wasn't until 1985 that the restored frieze was mounted in its permanent installation, which was designed to be similar to the original configuration. One wishes for a lesser degree of veracity; if only one could see it at eye level! I was taken by the composition, most of all. The vast expanses of soft, unadorned plaster punctuated, in a staccato rhythm with delicate figures. About halfway through, a dark, dense, fantastical arrangement of figures, including a serpent and an unexpected gorilla. Then: another soft passage, a few more figures and a final crescendo of lavish gold, patterning, and a couple locked in an embrace, diaphanous fabric falling around their ankles. It's stunning, and was marred only by the fact that the so-called climate-controlled room was cold and damp and reeked of cigarette smoke, presumably emanating from the surly guard.

I could not capture a decent photo of this magical performance, but here's a shot of the Musikverein. Cecelia Bartoli performed with Sol Gabetta and Cappella Gabetta. The program included works by Vivaldi, Handel, Gabrielli, Albinoni and Boccherini. During the concert, I was alternately crying and grinning ear to ear. What a night to remember!

Do yourself a favor: buy the album, Dolce Duello.

Last, but not least, the reason for this amazing journey: an invitation from Franz Mayer of Munich, architectural glass fabricators, to work for a week with their artists, in their amazing, historic Munich studio. I am so grateful for this opportunity and the chance to work amongst this renowned and talented group of people.

Franz Mayer of Munich was founded in 1847. The studio has produced some of the world's most successful public art over the years, in stained glass, glass mosaic and float glass. The range of techniques and possibilities is astonishing. I literally felt like I was entering a magical space, akin to Willy Wonka's Chocolate Factory: five floors of light and color, incredible work spaces, row upon row of colored glass (sheets stored in vertical bins, as well as mosaic pieces lining the hallways in rack after rack of numbered boxes) and works in progress by some of the world's most renowned artists. Together, we produced several samples that I will use for future public art proposals. We now have a sense of what it's like to work together; there is a big learning curve for both artist and fabricator, and it takes time to build a common language.

I did not want to photograph the studio's work in progress, out of respect for other artists, but here are a few photos of FMoM's stores of materials, as well as my samples in progress:

Luscious chunks of glass, as far as the eye can see.

Work in progress.

Me, looking up at the ceiling mirror in order to view work on the light table.

Hand-blown colored glass samples.

Printed sketch with color notations.

Hand-blown colored glass, replete with beautiful striations and bubbles.

Well, there you have it. Until next time!

A few years ago, I created a Stickies app list of artists' names on my laptop computer. At first, I thought of it as an imaginary exhibition, but I soon realized that it's actually a wishlist of artists whose work I would love to collect. I know many artists who own art. A few are successful enough to buy it outright, but most collect the work of artist friends, acquired through trade or received as gifts.

If you've been in my home, you know that it's incredibly compact. Nearly every wall is occupied by a window, door, appliance or piece of built-in furniture. We have one, and only one, wall that is large enough for a substantial work of art. What hangs on that wall? A large 1960s tapestry that once belonged to My Beloved's grandmother. She lived to be 106 years old, give or take a few years (she was coy about her age). I always loved the tapestry. It was made by Los Angeles artist John Smith and has the initials JS woven into the bottom edge. I don't know much about Smith, but he made large tapestries for Los Angeles banks and public buildings throughout the 60s. The tapestry hung for many years in Grandmother's Westwood apartment. When she moved into an assisted living facility, she gave the tapestry to me, much to the amusement of the rest of the family. In her old apartment, the piece was under-lit and a little shabby looking. The artist had stretched it over a folding stretcher bar frame. When I took possession of it, it was easy to remove a few screws, fold it in half, wrap it in plastic sheeting and tie it down in the bed of my old Ford pickup. As I recall, we did this on a hot summer day, and the tapestry "sweated" quite a bit in its plastic wrapping on the drive up Interstate 5 back to San Francisco. Of course, I had measured our wall, and was certain that the piece would fit, but when we got it up the stairs and into our flat, it seemed impossibly huge. However, my measurements were correct and it fit perfectly. It's held its place in our dining room for perhaps 12 years or so. I love it just as much as ever, mostly for the nostalgic associations that it evokes: mid-century California design; my undergraduate days at Scripps College, where such idealized imagery would not be entirely out of place amongst the early 20th century frescoes and mosaics found around campus; and the proto-feminist novel Herland, if perhaps it had been set in the 1960s or early 70s. I also love that it was a generous gift that made me feel like a real member of My Beloved's family.

Inevitably, when we have friends over for dinner, someone will ask, "Why don't you have one of your paintings there, instead of that?" Fair question. The answer: I live with my work, all day, everyday. If it is not in physical proximity, it is in my head, banging around, day and night. I really don't need to have it in front of me at all times. In fact, it is good and necessary to be away from it for a few hours a day.

Which brings me back to the subject of my imaginary art collection. What would I love to live with if I had more space to show art and a goodly sum of money to spend? You may have noticed that my imaginary budget is one million dollars. Sounds like a lot, right? Maybe, to some of you, it sounds like very little. If I had a smaller budget, I would probably buy the work of promising emerging artists. Of course, if I had a billion dollars and could buy anything I wanted, my list would be different, or at least more extensive. I would throw tens of millions at Roman antiquities, Picasso and Matisse, first- and second-generation Abstract Expressionism, German Expressionism, Allan McCollum, Jonathan Lasker, Sol Lewitt... ahh...fun to think about.

But, let's say I had a million dollars to spend, and I wanted to buy ten works of art. I am not an expert on prices or the market or the auctions. In writing this piece, I discovered that it is actually pretty difficult to find auction prices, unless you pay to view them. But there have been instances when I have seen price lists at galleries or art fairs and have been greatly surprised by the affordability of certain works by artists that I love, some of whom are on this list. Before I begin, a few things: 1) I do not know exact current values for each of these artists. Some of them have died in the last few years, so their prices may have risen or fallen; 2) my imaginary collection is comprised of things that I love and would love to live with. I have been thinking of most of these works for years--in some cases, nearly a decade; 3) these works are by artists who are well known, with solid careers, but I believe that most of them are somewhat undervalued.

Here they are, in no particular order.

Jay DeFeo, Untitled (Eternal Triangle series), 1980

On two separate trips to Santa Fe, NM in the last decade or so, I was lucky to see a pair of absolutely gorgeous Jay DeFeo exhibitions at Dwight Hackett Projects. DHP (now closed) was a fantastic venue, off the beaten track and away from the (mostly) schmaltzy offerings on Canyon Road. The first encounter was on the occasion of Jay DeFeo: No End: Works on Paper from the 1980s in 2006. We walked out of the blazing sun and into the cool garage-like space to find a gallery full of tightly-wound, gripping works on paper, along with a series of photographs, also by DeFeo. I was interested in the former, some of which were from the Eternal Triangle series. At the time, I wasn't familiar with DeFeo's works on paper. These works have a muscular, torqued quality about them. DeFeo was a master of form, and here she has taken the simple, primal form of a triangle and turned it up, down and inside out, revealing every edge, plane and the entirety of volume at once. There is a compressed, animated quality to these drawings, as if she has forced a several dozen animation cells to exist in a single frame. Some edges are jittery, some are succinctly incised. Some elements are transparent, while others are seemingly solid, all of them in a state of material flux that I find quite mesmerizing. As it turns out, the humble subject of these strong works is a simple, worn, kneaded eraser. According to Dana Miller's exhibition catalogue essay:

Jay DeFeo, Untitled (Eternal Triangle series), 1980

Untitled (Eternal Triangle series), 1980

Summer Landscape, 1982

In the early 2000s, the prices for these were around $30,000. They may have increased quite a bit since then, particularly since DeFeo's 2012 retrospective. Let's face it: I would love to own anything by DeFeo, but these works have really stayed with me for over a decade, so it's safe to say that I would probably enjoy living with one them for the rest of my life. I will close this section with a quote from the late Bill Berkson, who wrote extensively about DeFeo:

Nell Blaine, Abstraction, 1948-49